Acne Treatment During Pregnancy

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit, characterized by non-inflammatory (comedones) and inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, and nodules), which may lead to scarring and psychological distress. In women planning pregnancy or already in the gestational period, this condition can be particularly bothersome due to physiological changes and the unpredictable nature of acne during this time. Many women with acne experience improvement during the first trimester of pregnancy; however, a flare-up may occur in the third trimester, associated with increased androgen levels and higher sebum production. In addition to hormonal changes, immunologic shifts during pregnancy may also contribute. Inflammatory lesions tend to be more prevalent than non-inflammatory ones, often extending to the trunk. Patients with a history of acne are more likely to experience acne during pregnancy.

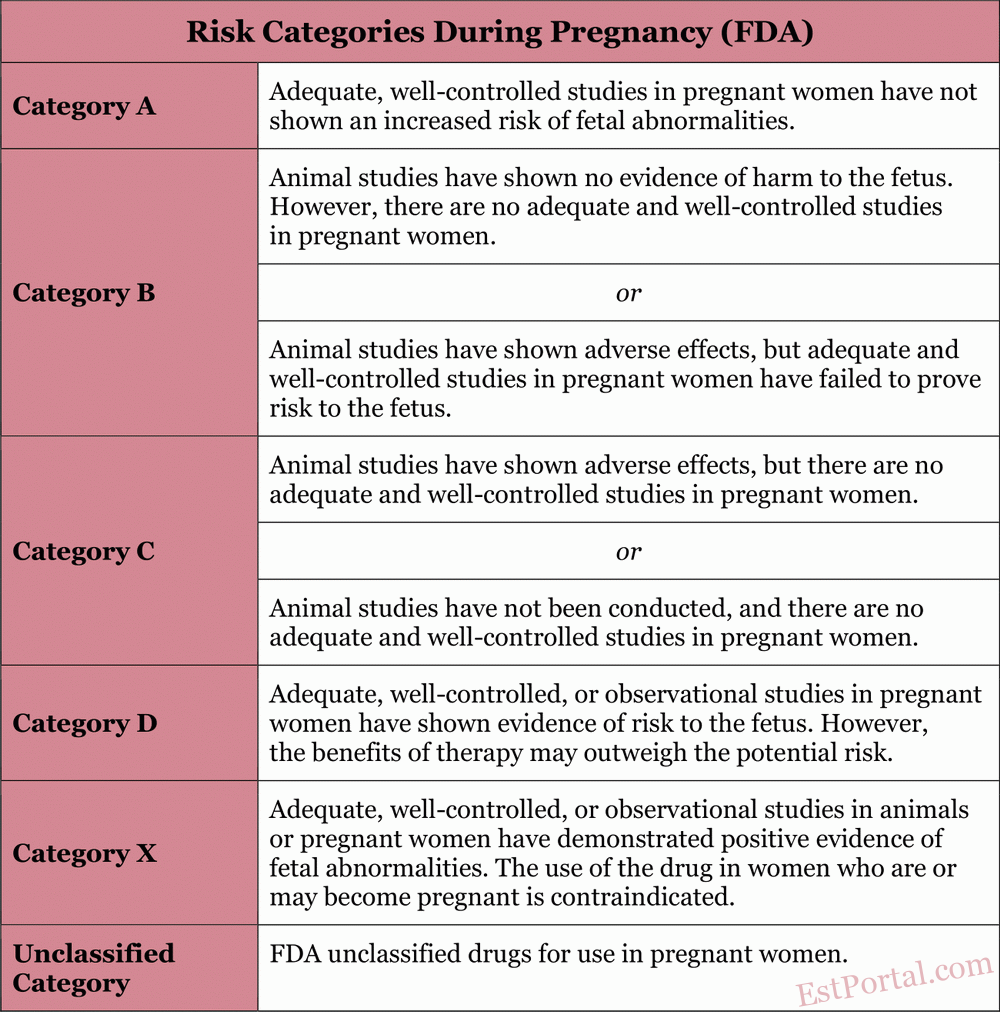

Treating acne during pregnancy can be challenging, as many commonly used and effective therapies are contraindicated or not recommended. Therefore, it is crucial for the prescribing physician to be aware of treatment restrictions during pregnancy, as outlined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [see Table 1].

Table 1

Due to inherent ethical concerns associated with the impossibility of conducting clinical trials during pregnancy, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data for evaluating the safety of medications during pregnancy are limited, and randomized controlled trials for acne treatments do not exist. Consequently, treatment recommendations during pregnancy are primarily based on observational studies and preclinical data obtained from animal models.

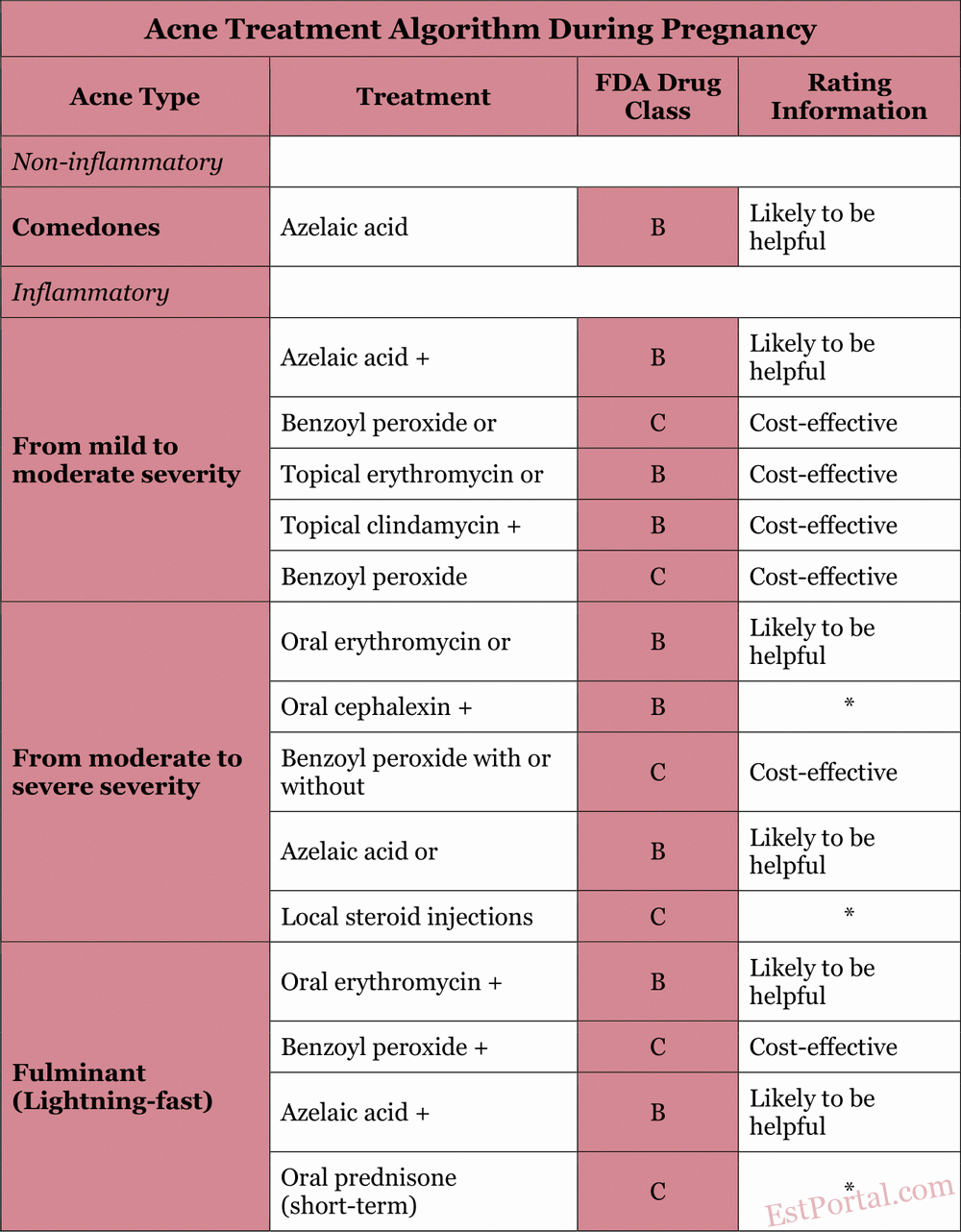

In this review, we will examine the safety and efficacy data of commonly used acne medications and outline a practical approach to managing acne during pregnancy, based on the most recent available evidence [see Table 2]. Armed with this information, physicians can develop a safe and effective treatment regimen for this unique patient population.

Table 2

Literature Search and Data Sources

For this review, a search was conducted in the PubMed database using the following key terms:

- acne;

- pregnancy;

- azelaic acid;

- benzoyl peroxide;

- salicylic acid;

- aminolevulinic acid;

- photodynamic therapy;

- FDA pregnancy.

No restrictions were applied to publication dates. The search included meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Additionally, searches were performed in the EMBASE, Cochrane, and UpToDate. databases.

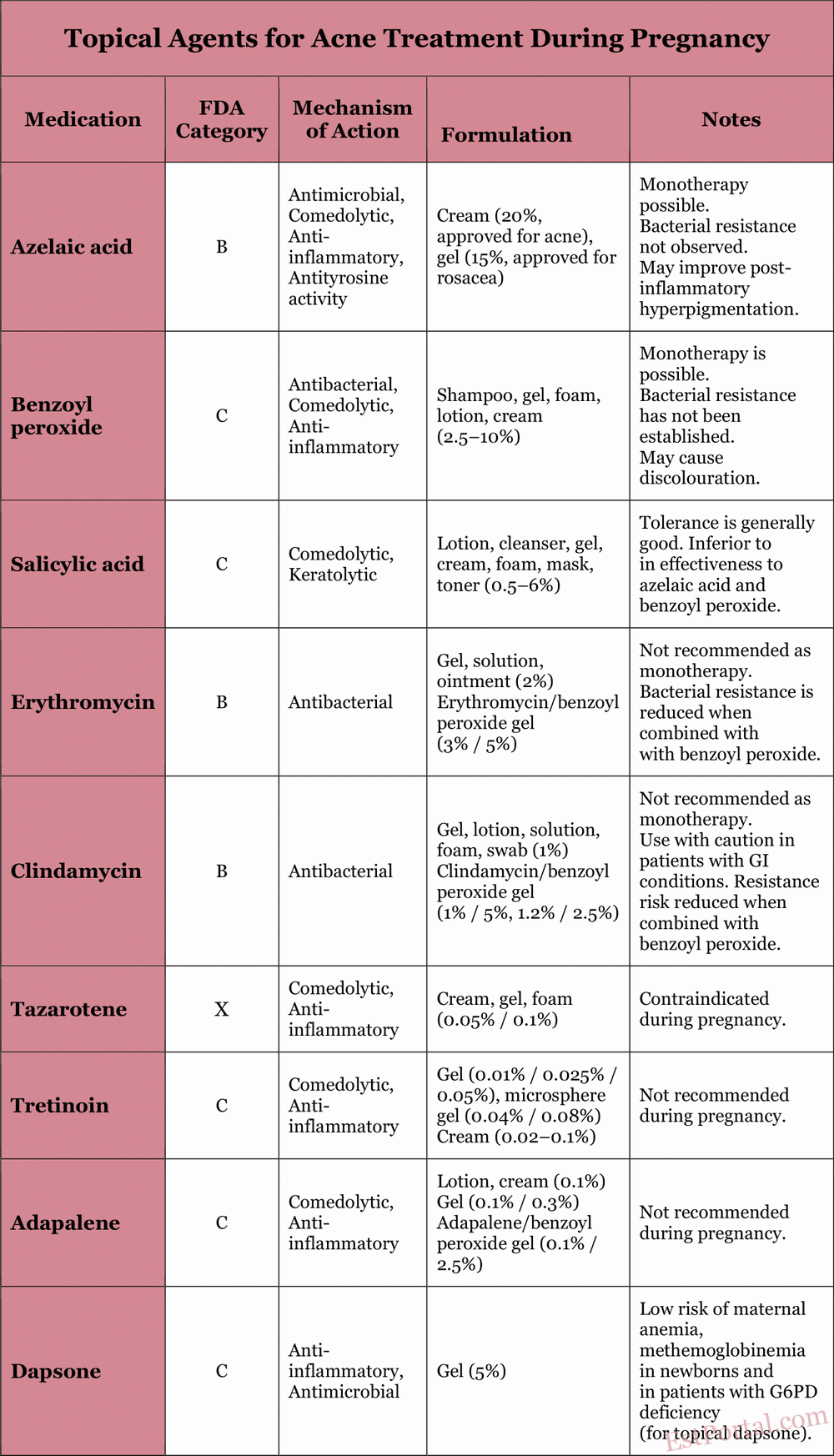

Topical Treatment

For mild to moderate acne, topical therapy is the standard of care. It is also an important component in the treatment of more severe acne and acts synergistically with oral agents. During pregnancy, the degree of systemic absorption of topical anti-acne agents must be carefully considered. The properties of commonly used topical agents are described in the following sections and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

Azelaic Acid

Azelaic acid is classified as a category B drug during pregnancy because animal studies have not shown teratogenic effects, and human data are lacking. Azelaic acid is a naturally occurring dicarboxylic acid with antimicrobial, comedolytic, and mild anti-inflammatory properties, and the added benefit of reducing post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. No resistance of P. acnes to azelaic acid has been reported. Approximately 4% of the drug is absorbed into the bloodstream after topical application.

Benzoyl Peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide is classified as a category C drug during pregnancy. Approximately 5% is absorbed systemically and is fully metabolized into benzoic acid, which is also known as a food additive. Due to its rapid renal clearance, no systemic toxicity is expected, and the theoretical risk of congenital anomalies is considered low. Benzoyl peroxide has antimicrobial, comedolytic, and anti-inflammatory effects. To date, no resistance of P. acnes to benzoyl peroxide has been observed. It is considered safe for use during pregnancy and helps prevent antibiotic resistance when used in combination with antibiotics.

Salicylic Acid

Salicylic acid is classified as a category C drug during pregnancy. There are no studies on topical use of salicylic acid in humans during pregnancy, although developmental abnormalities have been reported in rat embryos after systemic exposure to salicylic acid and aspirin administration during pregnancy. It is a keratolytic agent. The use of high concentrations of salicylic acid for skin hyperkeratoses has been associated with cases of salicylate toxicity; however, there are no known similar cases related to the use of salicylic acid in acne treatment. The risk during pregnancy is considered low when used on limited skin areas for short periods.

Topical Antibiotics

Topical antibiotics have long been used to treat inflammatory acne. Erythromycin and clindamycin are the two most commonly prescribed antibiotics for acne in pregnant women. Both are classified as category B during pregnancy. Short-term topical use of erythromycin and clindamycin is considered safe during pregnancy. However, there are no studies on the effects of long-term use. Given reports of pseudomembranous colitis caused by Clostridium species, topical clindamycin should be used with caution in patients with a history of gastrointestinal disorders. Topical clindamycin and erythromycin reduce P. acnes levels in sebaceous follicles by inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis, thereby controlling inflammatory acne. Combining topical antibiotics with benzoyl peroxide reduces the risk of resistance and increases treatment efficacy.

Topical Retinoids

Topical retinoids are derivatives of vitamin A and have been used to treat acne for more than 30 years. In the United States, commonly used agents include Adapalene, Tretinoin, and Tazarotene. Adapalene and Tretinoin are classified by the FDA as category C during pregnancy, while Tazarotene is classified as category X. This is partly due to the well-documented congenital defects associated with the use of systemic retinoid isotretinoin. Therefore, Tazarotene is not recommended for use during pregnancy.

Despite reports of potential congenital defects, topical Adapalene and Tretinoin are unlikely to cause birth defects due to their minimal dermal absorption. A recent meta-analysis ruled out any significant increase in the rates of miscarriage, congenital malformations, preterm birth, or low birth weight. Their mechanisms of action include accelerated keratinocyte differentiation, comedolytic, and anti-inflammatory effects. Nonetheless, these agents are not recommended during pregnancy, as their risk-benefit ratio remains uncertain.

Topical Dapsone

Topical dapsone is a synthetic sulfone with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. During pregnancy, it is classified as a category C drug. High doses in animal studies have not demonstrated teratogenic effects. To date, the use of topical dapsone during pregnancy has not been associated with an increased risk of birth defects. The risk of maternal anemia, as well as neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and hemolytic anemia, has been noted with oral use of dapsone in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, but the risk is low with topical application.

Topical dapsone was approved for acne treatment in 2005. Caution is advised due to its relatively recent introduction to the market and the lack of controlled studies confirming its safety in pregnancy. Dapsone is considered acceptable for topical use during pregnancy, but its safety has not been established in controlled trials. Use is advised only when the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk.

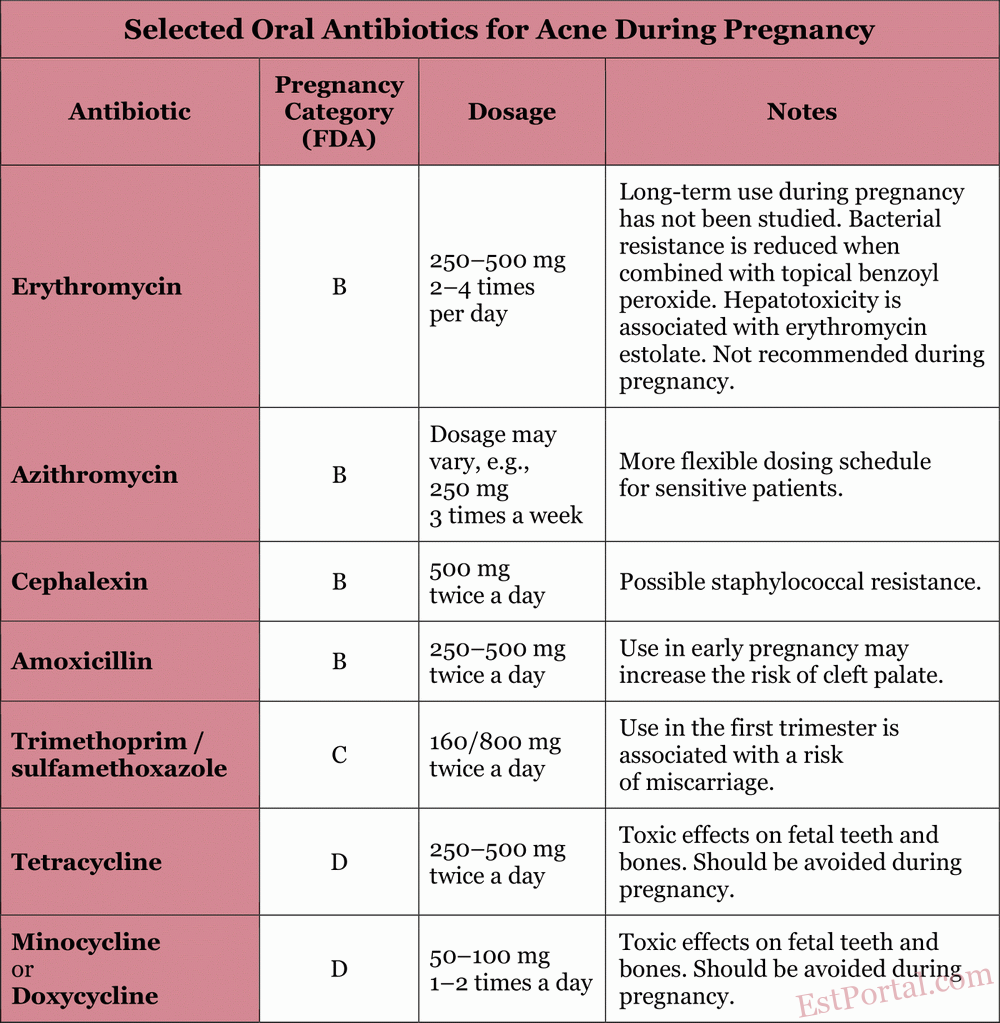

Oral Medications

Some patients are unable to achieve satisfactory results using topical treatments alone. Oral medications are primarily indicated for patients with moderate to severe inflammatory acne, as well as in cases where topical therapy proves ineffective. The properties of commonly used oral medications are described in the following sections and in Table 4.

Table 4

Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics improve inflammatory acne by inhibiting the growth of P. acnes within the pilosebaceous unit. Tetracycline-class antibiotics (including doxycycline and minocycline) exhibit both antibacterial and direct anti-inflammatory properties. The most commonly used antibiotics in patients (excluding pregnant women) are:

- Doxycycline;

- Minocycline;

- Erythromycin;

- Azithromycin;

- Cephalexin;

- Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole.

Due to rising bacterial resistance, it is generally recommended to combine topical benzoyl peroxide with oral antibiotics, limit their use to short courses, and avoid using oral antibiotics for maintenance therapy of acne. To minimize resistance, switching between oral antibiotics should be avoided when possible; if a particular oral antibiotic was effective in the past, it should be reused. Oral antibiotics should only be prescribed during pregnancy when clearly indicated.

Erythromycin is a macrolide classified as category B during pregnancy. The drug poorly crosses the placenta, resulting in low concentrations in fetal tissues. Erythromycin is generally considered safe during any stage of pregnancy when used for a few weeks. It can be considered the antibiotic of choice for treating severe inflammatory acne in pregnant women. However, its effects during long-term use (over 6 weeks) have not been studied. It is important to note that erythromycin estolate is contraindicated due to maternal hepatotoxicity.

Azithromycin is another macrolide classified by the FDA as category B during pregnancy. Animal studies have shown that azithromycin crosses the placenta without causing adverse effects on the fetus. Azithromycin is considered acceptable for use in pregnant patients with acne, although less safety data is available compared to erythromycin.

Amoxicillin is classified by the FDA as a category B drug during pregnancy. Its use in early pregnancy may increase the risk of cleft palate. Amoxicillin can be used alone or in combination with other medications as a treatment of choice for resistant acne. It may cause gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and vomiting.

Cephalexin is a first-generation cephalosporin with anti-inflammatory properties and is classified as category B during pregnancy. Cephalexin has not been associated with embryonic defects in animal studies. Although it is effective as an acne treatment, there are some concerns about the development of staphylococcal resistance to it.

Trimethoprim acts as a folic acid antagonist and is classified as category C during pregnancy. A recent study showed that the use of trimethoprim in the first trimester was associated with a doubled risk of miscarriage. Therefore, the use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole during pregnancy is recommended only when there are no alternatives and the benefits outweigh the risks.

Tetracyclines are classified as category D drugs during pregnancy. Animal studies have shown evidence of embryotoxicity and fetotoxicity, including toxic effects on fetal teeth and bones. Tetracyclines bind to calcium orthophosphate and therefore actively accumulate in teeth and bones. Deposits in the teeth persist for a long time, which leads to yellow discoloration of the deciduous teeth in children exposed to the drug after the 20th week of pregnancy, with progressive darkening over time. Bone deposition leads to reversible growth retardation of the fetus and inhibition of fibular bone growth, especially with long-term use. Tetracyclines should be avoided during pregnancy, particularly after the first trimester.

It is important to note that additional evidence is needed regarding the recommended duration of such treatments. The effects of long-term use of these antibiotics on the fetus remain unknown. These concerns should be weighed against the severity of acne and the availability of alternative topical treatments. The use of systemic antibiotics should be limited to the second and third trimesters, after organogenesis is complete, and treatment duration should be restricted to 4–6 weeks.

Oral Corticosteroids

The severity of treatment-resistant severe acne may significantly improve with the use of oral corticosteroids. According to the FDA, Prednisone is classified as category C during pregnancy. In animal studies, the drug has been associated with cleft palate, impaired brain growth, decreased myelination, and reduced head circumference. In humans, studies have shown an increased risk of cleft palate and a slight increase in miscarriage and preterm birth rates. There is limited data on the ability of systemic and topical steroids to cross the placental barrier, although it has been shown that topical steroids can have systemic effects.

Prednisone is prescribed only in exceptional cases — for severe fulminant acne after the first trimester, at minimal doses and for a limited course (no longer than 1 month). Use of steroids in the form of a small number of injections or short courses of oral corticosteroids for rare, rapidly progressing cases of acne vulgaris is unlikely to pose additional risk to the fetus. The dose of Prednisone should not exceed 20 mg per day, and the course duration should be limited to one month in late pregnancy.

Oral Retinoids

Isotretinoin is frequently prescribed to patients (excluding pregnant women) with persistent, conglobate acne vulgaris. The teratogenic effects of isotretinoin are well known, and it is classified as category X. The drug causes characteristic birth defects involving the craniofacial region, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, thymus, and parathyroid glands. Isotretinoin was approved in 1982 and works by reducing sebum production and normalizing keratinization. Isotretinoin is absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy.

Zinc

Zinc is an additional treatment option for pregnant patients with acne. Zinc sulfate is considered a category C drug during pregnancy, while zinc gluconate has not been officially classified. Animal and human studies, including those involving pregnant women treated for acne, have not shown an increased risk of fetal abnormalities or harm at doses below 75 mg/day. Zinc has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory properties and reduces sebum production. It has been shown to be effective in mild to moderate inflammatory acne when used as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. The recommended daily intake of zinc during pregnancy is 11 mg/day. Potential side effects include nausea and vomiting, typically dose-dependent.

Additional Therapy

Glycolic Acid

Glycolic acid falls under category N, meaning it is not classified for safety during pregnancy and is used topically for acne. There are no published reports of adverse effects associated with its use during pregnancy. Studies have shown improvement in inflammatory lesions and comedones, although closed comedones may respond more slowly. It also has additional benefits, including improvement of post-inflammatory changes and enhancement of skin absorption of topical medications.

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is classified as category C, with no animal studies available to evaluate its effect on reproductive function. Compared to control treatment, photodynamic therapy led to a statistically significant improvement in acne severity and showed sustained results up to 20 weeks of pregnancy after multiple sessions. Lack of insurance coverage and the frequency of in-office treatments may be limiting factors for use in pregnant women.

Conclusions

In this review, we have highlighted multiple treatment options for physicians who manage pregnant patients with acne. Below is a simplified algorithm that can serve as a starting point in selecting acne therapy during pregnancy.

For mild acne, characterized primarily by non-inflammatory lesions, a topical agent such as azelaic acid or benzoyl peroxide may be recommended as baseline therapy.

For inflammatory acne, it is advisable to initiate treatment with a combination of topical erythromycin or clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide.

For moderate to severe inflammatory acne, oral erythromycin or cephalexin may be prescribed, as both are considered safe when used for only a few weeks.

A course of prednisone not exceeding one month may be helpful in treating fulminant conglobate cystic acne after the first trimester. Typically, topical and oral antibiotics should not be used as monotherapy; to reduce bacterial resistance, they should be combined with topical benzoyl peroxide.

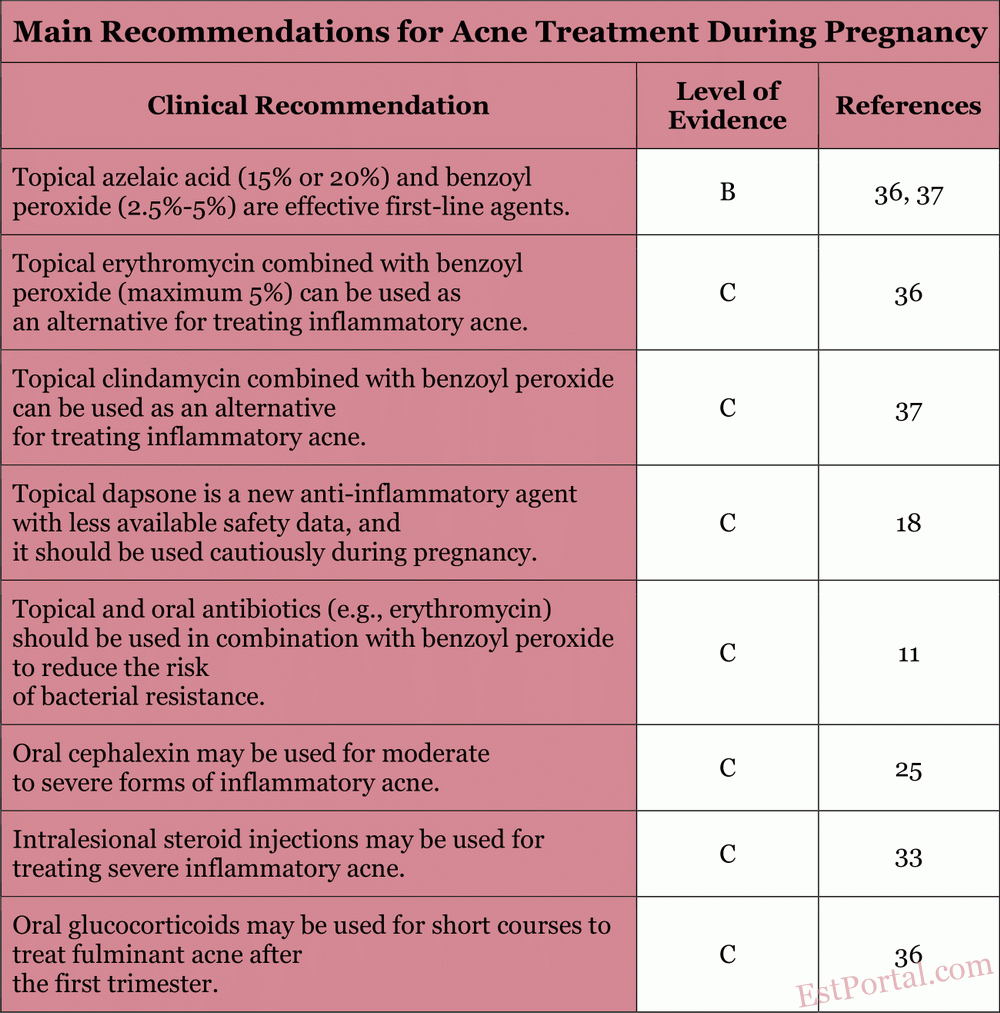

Additional therapies discussed in this review should be evaluated considering the patient's response and preferences. The main recommendations are summarized in Table 5. We hope this review proves useful for physicians managing acne in pregnant patients.

Table 5

The data presented may serve as a clinical guide in selecting safe and effective acne treatment during pregnancy, taking into account the gestational stage, severity of presentation, and individual characteristics of the patient.

References:

- Akhavan A, Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:473–92. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Jones SV, Ambros-Rudolph C, Nelson-Piercy C. Skin disease in pregnancy. BMJ 2014;348:g3489. FREE Full Text Google Scholar

- Pugashetti R, Shinkai K. Treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnant patients. Dermatol Ther 2013;26:302–11. PubMed Google Scholar

- Dréno B, Blouin E, Moyse D, Bodokh I, Knol A, Khammari A. Acne in pregnant women: a French Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:82–3. PubMed Google Scholar

- Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive dermatologic drug therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012. Google Scholar

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. Pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:401.e1–14; quiz 415. Google Scholar

- Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 2012;379:361–72. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Parry MF, Rha CK. Pseudomembranous colitis caused by topical clindamycin phosphate. Arch Dermatol 1986;122:583–4. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Siegle RJ, Fekety R, Sarbone PD, Finch RN, Deery HG, Voorhees JJ. Effects of topical clindamycin on intestinal microflora in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15(2 Pt 1):180–5. PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Patel M, Bowe WP, Heughebaert C, Shalita AR. The development of antimicrobial resistance due to the antibiotic treatment of acne vulgaris: a review. J Drugs Dermatol 2010;9:655–64. PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Kinney MA, Yentzer BA, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR. Trends in the treatment of acne vulgaris: are measures being taken to avoid antimicrobial resistance? J Drugs Dermatol 2010;9:519–24. PubMed Google Scholar

- Berard A, Azoulay L, Koren G, Blais L, Perreault S, Oraichi D. Isotretinoin, pregnancies, abortions and birth defects: a population-based perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:196–205. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Panchaud A, Csajka C, Merlob P. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to topical retinoids: prospective study. J Clin Pharmacol 2012;52:1844–51. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

- Kaplan YC, Ozsarfati J, Etwel F, Nickel , Nulman I, Koren G. Pregnancy outcomes following first trimester exposure to topical retinoids : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2015;173:1132–41. PubMed Google Scholar

- Gamble R, Dunn J, Dawson A, et al. Topical antimicrobial treatment of acne vulgaris: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012;13:141–52. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

- Nosten F, McGready R, d'Alessandro U, et al. Antimalarial drugs in pregnancy: a review. Curr Drug Saf 2006;1:1–15. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

- James KA, Burkhart CN, Morrell DS. Emerging drugs for acne. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2009;14:649–59. PubMed Google Scholar

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs 2013;73:779–87. PubMed Google Scholar

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne Group. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1–50. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Romoren M, Lindbaek M, Nordeng H. Pregnancy outcome after gestational exposure to erythromycin-a population-based register study from Norway. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:1053–62. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

- Al Hammadi A, Al-Haddab M, Sasseville D. Dermatologic treatment during pregnancy: practical overview. J Cutan Med Surg 2006;10:183–92. Google Scholar

- Hale EK, Pomeranz MK. Dermatologic agents during pregnancy and lactation: an update and clinical review. Int J Dermatol 2002;41:197–203. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Lin KJ, Mitchell AA, Yau W-P, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S. Maternal exposure to amoxicillin and the risk of oral clefts. Epidemiology 2012;23:699–705. PubMed Google Scholar

- Turowski CB, James WD. The efficacy and safety of amoxicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and spironolactone for treatment-resistant acne vulgaris. Adv Dermatol 2007;23:155–63. PubMed Google Scholar

- Fenner JA, Wiss K, Levin NA. Oral cephalexin for acne vulgaris: clinical experience with 93 patients. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25:179–83. PubMed Google Scholar

- Andersen JT, Petersen M, Jimenez-Solem E, et al. Trimethoprim use in early pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage: a register-based nationwide cohort study. Epidemiol Infect 2013;141:1749–55. Google Scholar

- Park-Wyllie L, Mazzotta P, Pastuszak A, et al. Birth defects after maternal exposure to corticosteroids: prospective cohort study and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Teratology 2000;62:385–92. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Rennick GJ. Use of systemic glucocorticosteroids in pregnancy: be alert but not alarmed. Australas J Dermatol 2006;47:34–6. CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar

- Gur C, Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Arnon J, Ornoy A. Pregnancy outcome after first trimester exposure to corticosteroids: a prospective controlled study. Reprod Toxicol 2004;18:93–101. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- Dréno B, Blouin E. [Acne, pregnant women and zinc salts: a literature review]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2008;135:27–33. PubMed Google Scholar

- Brocard A, Dréno B. Innate immunity: a crucial target for zinc in the treatment of inflammatory dermatosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:1146–52. PubMed Google Scholar

- Brandt S. The clinical effects of zinc as a topical or oral agent on the clinical response and pathophysiologic mechanisms of acne: a systematic review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol 2013;12:542–5. PubMed Google Scholar

- Taub AF. Procedural treatments for acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:1005–26. PubMed Google Scholar

- Hongcharu W, Taylor CR, Chang Y, Aghassi D, Suthamjariya K, Anderson RR. Topical ALA-photodynamic therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 2000;115:183–92. CrossRef PubMed Web of Science Google Scholar

- de Leeuw J, van der Beek N, Bjerring P, Neumann HAM. Photodynamic therapy of acne vulgaris using 5-aminolevulinic acid 0.5% liposomal spray and intense pulsed light in combination with topical keratolytic agents. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24:460–9. PubMed Google Scholar

- Dréno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27:1063–70. PubMed Google Scholar

- Purdy S, de Berker D. Acne vulgaris. BMJ Clin Evid 2011;2011. pii. 1714. Google Scholar

Authors: Anna L., Chen A., Qi C., Reiner B., Sachs D., Helfrich I. (Johns Hopkins University, University of Michigan, USA)

Based on materials from JABFM